Photo Credit: Tim Fitzharris/Getty

Special thanks to Michelle Nijhuis @nijhuism • February 10, 2014, for providing this information!

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service relied on shaky science in its effort to boot wolves off the Endangered Species List. Here’s the full story behind the biological brouhaha.

“About 300 wolves live in the nearly 2-million-acre swath of central Ontario forest known as Algonquin Provincial Park. These wolves are bigger and broader than coyotes, but noticeably smaller than the gray wolves of Yellowstone. So how do they fit into the wolf family tree? Scientists don’t agree on the answer—yet it could now affect the fate of every wolf in the United States.

That’s because last June, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed removing gray wolves across most of the country from the endangered species list, a move that would leave the animals vulnerable to hunting. To support its proposal, the agency used a contested scientific paper—published, despite critical peer review, in the agency’s own journal—to argue that gray wolves never existed in the eastern United States, so they shouldn’t have been protected there in the first place.

Instead of the gray wolf, the service said, an entirely different species of wolf—the so-called “eastern wolf,” a species whose remnants perhaps survive in Algonquin Park—once inhabited the forests of eastern North America. Canid biologists have argued over the existence of this “lost species” for years. Yet researchers on all sides say that even if the Algonquin wolves are a separate species, that shouldn’t preclude continuing protections for the gray wolf.

On Friday, an independent panel of five leading geneticists and taxonomists came down hard on the agency’s proposal to delist gray wolves, unanimously concluding that the service had not relied on the “best available science.” Individual panel members described “glaring insufficiencies” in the supporting research and said the agency’s conclusions had fundamental flaws.

“What’s most significant,” says Andrew Wetzler, director of land and wildlife programs for the Natural Resources Defense Council (which publishes OnEarth), “is that this is coming from a group of eminent biologists who disagree with each other about the eastern wolf—and even so, they agree that the agency hasn’t properly understood the scientific issues at hand.”

* * *

How did 300 wolves in the Canadian wilderness become central to the debate over protecting their U.S. relations? For years, the Algonquin Park wolves have been something of a scientific mystery. Their coats are typically multicolored, with reddish-brown muzzles and backs that shade from white to black. Visitors from the southeastern U.S. often note their resemblance to red wolves, which are limited to a small reintroduced population in eastern North Carolina.

As biologists began to investigate the relationships among the various North American canids, including Algonquin wolves, red wolves, coyotes, and gray wolves, they collided with one of the most basic—and vexing—questions in their field: what is a species?

“No one definition has as yet satisfied all naturalists,” Charles Darwin himself conceded in On the Origin of Species, adding that “every naturalist knows vaguely what he means when he speaks of a species.” So do the rest of us. We know that hippos are different from canaries, and that bullfrogs are different from giant salamanders. But the more alike the organisms, the trickier the species question becomes, and thanks to our modern understanding of DNA, the scientific disagreements are—if anything—more passionate today than in Darwin’s time.

In 1942, the biologist Ernst Mayr formalized the definition of a species as a group of interbreeding organisms, reproductively isolated from other interbreeding groups. That’s the definition that most of us learned in high-school biology, and it remains useful in many cases. But the advent of cheap, fast DNA analysis has exposed its limits: many apparently distinct species hybridize with one another, and few animals hybridize more enthusiastically than wolves, dogs, and other canids.

Genetic samples from the Algonquin Park wolves contain what appears to be coyote DNA, gray wolf DNA, and even domestic dog DNA, creating what Paul Wilson of Trent University in Ontario, one of the first scientists to study the Algonquin Park population, calls a “canid soup” of genetic material.

Biologists studying North American canids fall generally into two camps. Wilson and several of his colleagues in Canada support what’s sometimes called the “three-species” model: according to their interpretation of the genetic data, coyotes, modern gray wolves, and the eastern wolf are separate species that evolved long ago from an ancient common ancestor. The eastern wolf, they say, may have once ranged throughout eastern North America, and may in fact be the same species as the red wolf.

Other biologists, including canid geneticist Robert Wayne at the University of California-Los Angeles, support a “two-species” model: it posits that only gray wolves and coyotes are distinct species. According to this model, anything else—a red wolf, Algonquin wolf, or the so-called “coywolf” recently spotted in suburbs and cities—is a relatively recent wolf-coyote hybrid.

Wayne describes the debate between supporters of the two models as “long-running but very polite”—and it’s not over yet.

“People on all sides have done some very good work, but it’s an extremely complicated issue,” says T. DeLene Beeland, author of The Secret World of Red Wolves. “It gets at the heart of the species question.”

* * *

Were it not for the U.S. Endangered Species Act, the controversy over the eastern wolf might well have stayed polite. That landmark law is, as it states, intended to protect species, and the murky definition of a species has complicated conservation efforts for jumping mice, pygmy owls, gnatcatchers, pocket gophers, and several other animals. But the debate over wolf taxonomy has become especially fierce.

When the gray wolf was placed on the endangered species list in 1967, it was defined as a single species with a historic range that covered most of the United States, from Florida to Washington state. Hunting, trapping, poisoning, and habitat loss had driven the gray wolf nearly to extinction in the continental United States, and confirmed sightings were rare.

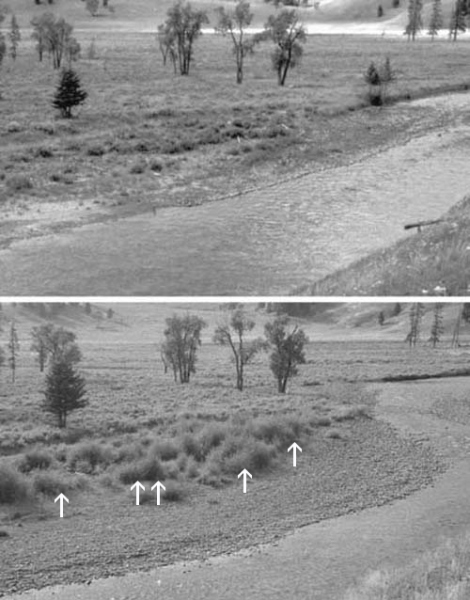

After the species was protected, wolves from western Canada began to venture south, and beginning in 1995, some 41 wolves were reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park. They multiplied rapidly, and for the first time in decades, wolf howls were heard in the park. Today, many consider the Yellowstone wolf reintroduction one of American conservation’s greatest success stories.

In 2011, the Fish and Wildlife Service took the Great Lakes wolf population off the endangered species list. The same year, a controversial act of Congress delisted gray wolf populations in most of the Rocky Mountains, returning responsibility for wolf protection to the states. But wolves are famously energetic travelers, and these wolves didn’t stay put. In recent years, wolves from the northern Rockies have been spotted in Washington, Oregon, and northern California, and are rumored to be ranging into Colorado and Utah. Wolves from the Great Lakes have turned up in Illinois and Iowa.

“The reason why wolves became in endangered in first place is that states allowed people to hunt the hell out of them.”

Outside the northern Rockies and the Great Lakes, wolves are still protected by the Endangered Species Act, so these wanderers have raised delicate political questions. Although some states are willing to work with the federal government on wolf management, others want sole control of any wolves that turn up within their boundaries. And the White House’s slim margin of support in the Senate relies on centrist Democrats from Western states—many of whom support full wolf delisting, in part because some Western ranchers want the right to shoot wolves that menace their livestock.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, for its part, wants to devote its limited money and resource to conservation of the Mexican wolf, a type of gray wolf that was reintroduced into northern New Mexico and Arizona in 1998 and continues to struggle for survival. “The time has now come for the service to focus its efforts on the recovery of the Mexican wolf,” agency director Dan Ashe said at a public hearing last year in Washington, D.C.

The Fish and Wildlife Service proposed removing the rest of the country’s gray wolves from the federal endangered species list last June, protecting only the Mexican wolf as an endangered subspecies. Any gray wolves that roamed beyond the northern Rockies and the Great Lakes, it announced, would no longer enjoy endangered species protection. The delisting proposal set off a contentious public comment period that was due to end in September, after which the delisting would either be finalized or scrapped.

One part of the agency’s proposal was especially unusual: it argued that its original listing of the gray wolf, back in 1967, had been flawed. In the delisting proposal, the agency not only recognized the eastern wolf as a separate species but also concluded that its existence required a major revision to the historic range map of the gray wolf—making it far smaller than the initial listing had claimed.

Agency director Ashe argued at the hearing in Washington, D.C., last September that there is “no one set formula for how to recover a species.” The law requires only that species be safe from extinction, he said, not restored throughout its historic range, before it can be taken off the endangered species list. The two thriving populations in the Great Lakes and Rocky Mountains, the agency said, were reason enough to delist the gray wolf.

But historic range has long been an important factor in delisting decisions. “If you eliminate the entire East Coast from the gray wolf’s range map, it’s just much easier to argue that wolves are no longer endangered,” says NRDC’s Wetzler.

At the D.C. hearing, Don Barry, who served as an assistant Interior secretary during the Clinton administration, took the microphone to speak for himself and two other former assistant secretaries. Barry recalled that the bald eagle, American pelican, American alligator, and peregrine falcon had been removed from the endangered species list only after returning to suitable habitat throughout most of their historic ranges.

“That is how the Endangered Species Act is supposed to work,” said Barry. By stark contrast, he said, the proposal to delist the gray wolf reflected “a shrunken vision of what recovery should mean.”

* * *

The Fish and Wildlife Service is required to back up its decisions with science, but in this case, the science was hard to come by. When the agency recognizes new species, for instance, it usually relies on the judgment of scientific organizations such as the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature—which doesn’t recognize the eastern wolf as a separate species. Neither does any similar scientific group.

So instead, the agency relied on a 2012 study by Steven Chambers, a Fish and Wildlife Service staff biologist, and three of his agency colleagues. The Chambers study had already caused controversy: it was published in a recently revived agency journal, not a standard scientific journal. When outside researchers reviewed the paper, the majority had significant criticisms, with one going so far as to say that the study’s argument “is made in an intellectual vacuum.” Although the journal’s editors asked Chambers to respond to the critiques, the revised paper was not resubmitted to reviewers, as it would have been at a standard journal.

In 2012, the agency cited the Chambers paper in a proposal to remove the Great Lakes wolf population from endangered species protection. The agency had to remove the citation after outcry from other scientists in the field and acknowledged at the time that the study “represents neither a scientific consensus nor the majority opinion of researchers on the taxonomy of wolves.”

Two years later, though, the agency once again used the Chambers paper, this time to support the removal of all federal protections for wolves.

When outside researchers reviewed the paper, the majority had significant criticisms, with one going so far as to say that the study’s argument “is made in an intellectual vacuum.”

“There’s a lot wrong with the process that the Fish and Wildlife Service used that led to the development of the Chambers paper, and to its subsequent policy decisions,” says Sylvia Fallon, a senior scientist at NRDC. (Agency officials did not respond to requests for comment on this story.)

Fallon and many other conservationists are also critical of the agency’s review process for the delisting proposal itself. Whenever the agency proposes a change to the status of a species, it is supposed to rely on the “best available science.” To make sure it is doing that, it convenes an independent review panel of experts to critique the agency’s reasoning.

But this past summer, three respected wolf biologists were dropped from the review panel; all of them had signed a letter opposing the designation of the eastern wolf as a distinct species. “We were delisted,” jokes UCLA’s Wayne, one of the excluded scientists. The resulting public outcry forced the agency to extend its comment period and convene a second panel in September. This time, Wayne was on it, along with NRDC’s Fallon. So was one of the leading supporters of the “lost wolf” theory, Trent University’s Paul Wilson.

Despite their continuing disagreement over the provenance of the Algonquin Park wolves, the peer reviewers were unanimous in their verdict on the agency’s science. The proposal was too dependent on the Chambers paper, they said, and the paper’s central argument was far from universally accepted.

Wolf geneticists also disagree with agency’s use of the eastern wolf as support for shrinking the gray wolf’s historic range. The two could easily have existed side by side, they say. In fact, historical accounts from New York State describe two distinct types of wolves—one smaller and more common, the other larger, heavier, and rarer.

* * *

On Friday, when the Fish and Wildlife Service released the review panel’s report, the agency also issued a brief statement extending the comment period on the delisting proposal until late March—after which the agency will decide whether and how to continue with the delisting effort.

With the comment period reopened, conservationists are again arguing that the full, nationwide delisting of the gray wolf is too much, too soon, and not supported by current science. The Northern Rockies population fell 6 percent in the year after Congress removed wolves there from the endangered species list—a drop due largely to the revival of wolf hunting. Idaho Governor Butch Otter is now supporting a billthat would reduce the number of wolves in his state from about 680 to just 150. Advocates fear the same response in other states where wolves lose federal protection.

“The reason why wolves became in endangered in first place is that states allowed people to hunt the hell out of them,” says Bill Snape, a veteran endangered species lawyer who now works for the Center for Biological Diversity. “Why, after years of effort and a lot of success, would we hand the key right back to the entities that got us in hot water in first place?”

Snape acknowledges that “no one wants wolves to stay on the endangered species list forever,” but he points out that the agency could take a more measured approach to delisting, as it has done with other high-profile species.

Whatever path the agency chooses, says NRDC’s Wetzler, it needs to heed the warnings of the expert panel and stick to the science. “It’s not that the agency has bad intentions, or bad scientists. It’s that the idea that gray wolves never existed on the East Coast of the U.S. was a very convenient result—it matched up nicely with their view of wolf recovery and what they wanted to do.

“It’s very easy to get caught up in your own story.”

This article was made possible by the NRDC Science Center Investigative Journalism Fund.

Read Full Post »